Retribution is the key to liberation.

For our ancestors and for us.

Is all violence created equal? Is there a difference between an abuser killing his victim and a victim killing their abuser? Is there a difference between the enslaved killing their master and the master killing the enslaved? Which one is worse? Can any of it be justified?

Retribution can balance the scales and liberate the oppressed from cruelty. Retribution functions as a severing of ties with that cruelty, allowing those oppressed to reclaim power, autonomy, and ultimately, liberation.

These individual acts of retributive violence do not carry the same moral weight as systemic, institutional violence or the violence one faces from an abuser. However, the acts do yield something more important: powerful results towards achieving one’s liberation.

Phillip Hallie was an American scholar, professor, and ethicist. In his work From Cruelty to Goodness, Philip Hallie explores and defines cruelty, goodness, and institutionalized harm. His work on cruelty begins with a deceptively simple but distinctly important observation: cruelty is a power relationship. In this work, he writes:

“Cruelty then, whatever else it is, is a kind of power relationship, an imbalance of power wherein the stronger party becomes the victimizer and the weaker becomes the victim. And since many general terms are most swiftly understood in relationship with their opposite sites (just as ‘heavy’ can be understood most handily in relationship with what we mean by ‘light’), the opposite of cruelty lay in a situation where there is no imbalance of power. The opposite of cruelty, I learned, was freedom from that unbalanced power relationship. Either the victim should get stronger and stand up to the victimizer, and thereby bring about a balance of their powers, or the victim should free himself from the whole relationship by flight.”

To Hallie, cruelty is not just isolated acts of harm, but a sustained experience in which one party dominates and the other suffers. To Hallie, the essence of cruelty lies in imbalance. The stronger imposes its will, the weaker is subjugated. Some just plainly call this a power dynamic, however cruel. When discussing what the opposing force of cruelty is, Hallie says that the opposite of cruelty is not kindness or empathy, as dictionary antonyms would tell you. He even goes on to say that kindness could be the ultimate cruelty in some circumstances.

Instead, Hallie says the opposite of cruelty is freedom from a cruel relationship.

To Hallie, freedom can take one of two forms. The victim can grow strong enough to confront the oppressor, thereby restoring balance, or the victim can remove themselves entirely from the structure that perpetuates harm (also known as fleeing). Nevertheless, it is liberation.

When describing cruelty, Hallie makes the distinction clear. Cruelty is not in isolated acts of violence (which he refers to as episodic violence). It is a relationship of domination that grinds down the spirit of its victim (especially over time and through institutions). Cruelty (as it’s institutionalized and enduring) is not the same as violence (as it is episodic).

It is not the lash of a whip, but a drawn out system that convinces the oppressed that the whip is natural, deserved, or inescapable. The lash of the whip is violence. The cruelty is a system. It’s a system that convinces you to have empathy for the oppressor who commits or incites violence against you. Cruelty is a system that actively harms you while touting “violence is never the answer.” Institutionalized cruelty works by embedding suffering into the very structure of your life and your psyche, until you, the oppressed or the victim, carry the weight of your own degradation. Institutionalized cruelty works by forcing you to buy into fake moral systems to be viewed amicably by the oppressive dominant culture. Institutionalized cruelty is a system that brainwashes, incites violence, manipulates, confuses, and more. It’s a system that forces you to fight off zombie like grappling claws, sometimes from your own class and race, their nails raking your forearms as they enforce the oppressor’s cruelty, leaving you to inch and struggle toward liberation. Under institutional cruelty, every inch of freedom is fought for because it seeps into every inch of your life.

That is institutional cruelty.

However, against this cruelty, Hallie believes hospitality, empathy, and care are the solution.

He speaks to communities that sheltered Jewish people during the Nazi occupation as an example of this ethic. According to Hallie, resistance through nonviolent compassion preserves dignity and refuses to mirror cruelty. His line of thinking aligns quite well with what many already think — that one can act morally under oppression without succumbing to the oppressor’s methods, and if not, they are “morally compromised.”

Now, here is where I diverge from Hallie’s word. This is where we full stop.

Hallie effectively misses the imbalanced dynamics of power, akin to when people claim reverse racism and uphold white supremacist ideals as the baseline.

He does not carry the dismantling framework that liberation requires. There’s a difference between exiting, fleeing, and dismantling. Institutions must be dismantled.

The idea of the oppressed “compromising integrity” assumes a moral standard rooted in white supremacist ideals of what’s virtuous and moral. It holds the oppressed accountable to the oppressor’s ethics, and in doing so, further supports institutionalized cruelty.

Whose dignity are we preserving? If white supremacists define it, are we still centering their ideals of righteousness and virtue? Well, yes.

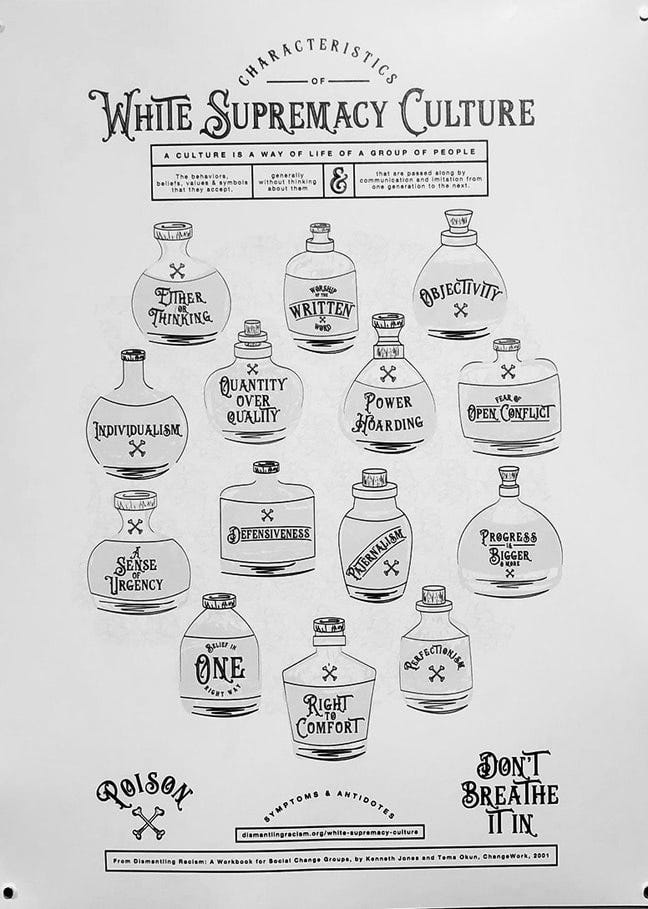

See: Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture.

What Hallie frames as moral survival (which is just maintaining dignity by refusing to mirror cruelty) preserves ethical alignment with white centered ideas. But liberation requires reclaiming power, disrupting oppressive systems, and sometimes seeking justice in ways that defy conventional norms and look messy from a traditional moral or “virtuous” perspective.

What does that mean for the oppressed? The bar is different.

The oppressed are not morally failing or mirroring by resisting or even responding forcefully. They are navigating a radically inequitable power landscape that Hallie completely overlooks —which is quite odd for someone discussing power dynamics.

Truly, the dynamics of the oppressed and oppressors are fundamentally different, so they can’t mirror each other. The oppressed cannot subjugate the oppressor in the same way, because the foundation of their power (or lack thereof) is unequal. It’s not a mirror. Hallie effectively misunderstands the structural imbalance that underlines and defines oppression.

There is no “attempting to replicate the methods of cruelty.” It’s not possible to replicate the institutionalized cruelty he speaks of during the process of resistance or retribution.

He does acknowledge that episodic violence is not the same as the institutionalized cruelty that defines one’s oppression, but struggles with the next step. Oppressed people cannot truly enact institutionalized cruelty, because oppressed people lack the systemic power to enforce it! Likewise, reactive abuse does not replicate the structures that sustain their harm. Therefore, “violent” actions all carry a fundamentally different weight. It’ll never…look..or be..the same.

P.S. All actions are not ethically equal, actually.

And I get it, Hallie’s entire thing is empathy. But here’s the thing:

Empathy does not dismantle power imbalances.

Don’t get me wrong, community care, empathy, and solidarity are necessary acts of resistance to cruelty. However, that care is meant to sustain and nourish the community members. These ideals help us push through, but empathy does not directly free anyone from institutional cruelty or systemic violence.

Why? Because institutions do not feel, and, as Hallie himself said,

“The sword does not feel the pain that it inflicts. Do not ask it about suffering.”

These systems may acknowledge morals and emotional sentiment, but they rarely yield it as a force. Oppressors may urge the masses to cling to moral sentiments like empathy as a check against evil, but they never actually rely on it themselves to gain power or advance strategy. They advance their strategies using violence instead.

Paul Hallie swears by empathy as the ultimate counter to cruelty.

In all of this, he seems to confuse moral survival in the face of cruelty (maintaining your ethical integrity, your sense of right and wrong, your capacity for empathy and decency) with real-life liberation. Maintaining dignity by resisting cruelty may make sense in interpersonal conflict, but moral survival alone is insufficient for widespread liberation and institutional upheaval. Reminder:

“The opposite of cruelty, I learned, was freedom from that unbalanced power relationship. Either the victim should get stronger and stand up to the victimizer, and thereby bring about a balance of their powers, or the victim should free themselves from the whole relationship by flight.”

To truly end cruelty, the oppressed must do more than endure it through grace or fleeing. The oppressed must break the relationship of domination itself, and “stand up” as Hallie states.

That is where retribution enters.

“Retribution is a rational, proportional, and institutional process focused on justice.”

Retribution is not petty vengeance or an attempt to mirror oppression. It is a moral act that severs the cruel tie that Hallie speaks of. When institutional cruelty dehumanizes, retribution rehumanizes by reclaiming agency and power. (Because lord knows the quickest way to oppress is to strip one of their humanity and identity. That’s a conversation for another day.) However, retribution declares that the relationship is over, that the oppressed will no longer live under the oppressor’s terms or by their rules, whether morally, lawfully, physically, or anything else.

That’s why withholding empathy from a white supremacist who just died is jarring to white dominant culture and those seeking favor within it. In denying the oppressor the grace and empathy they expect, those harmed or victimized assert their autonomy, breaking the cycle and severing just one cruel tie. It may seem like nothing, but it severs a cruel and crucial tie.

‘Institutional cruelty,’ as Hallie so passionately coined, exists to maintain domination. It exists to erase individuality and enforce submission. Retributive action by the oppressed exists to end this domination and reclaim freedom.

The origins, function, and meaning of the actions are fundamentally different, so their moral weight cannot be the same. If anything, refusing such retribution may preserve cruel structures.

Empathy leaves that painful sword that Hallie speaks of, perfectly intact. Retribution, on the other hand, is a defiant act of severance and an ethical one at that. Retribution is the blade that severs the bond between oppressor and oppressed. It is decisive, consequential, and final. Retribution (or what some may label as resistance) challenges and subsequently ends the cruelty, not without a fight, but it does.

It’s how our ancestors were freed, and it’s how every other oppressed group around the world was and will be freed, too. That’s just history and the future.

Hallie rightfully names freedom from the cruel relationship as the opposite of cruelty. For that, I applaud him and uplift this section of his work. However, it so gravely falls short in defining what freedom from cruelty truly requires for people like me.

Nonetheless, retribution still fulfills Hallie’s principle of freeing from the cruel relationship. It effectively breaks the unbalanced power and restores autonomy and dignity where both have been stripped away. Retribution is functional, and it’s how the oppressed reclaim their power from this institutionalized cruelty. Always has been, always will be.